In all my eleven years, I'd never heard such a sound. One minute there was only the ordinary bustling chatter of the crowd around us on the midway, and then it began-a wild ululation that ran up and down the scale and off into shivery highs and lows that I somehow knew only my sensitive ears could really hear. My throat began to hurt in sympathy, and chills crawled up my backbone.

The instant look of sorrow on Papa's face told me he heard something too, and he worried that it was a cry of pain. But I knew right away it was anger-pure, white-hot, blood-boiling anger.

The crowd of marks looked around, a few smelling scared, most just looking puzzled. It was after noon, almost time for the Clark/Dawson Circus matinee show. Papa and I had traveled here to have some fun, as well as for Papa to compare this show to ours. I'd been looking forward to a good time, just me and Papa, while Pa kept things running at our show, camped a few miles away. Now all thoughts of pleasure were gone, wiped out of my head by that unearthly, heart-twisting call.

Papa let go my hand as he turned, urgent, to speak to the man in the nearby barker's booth. I didn't stop to think; I just slipped away from the busy midway of the strange show and moved instinctively toward the hot, keening cry that pulled at me like a hook and line.

The little tent I found, hidden back behind all the others, smelled familiar somehow, sharp with old piss and sweet-sour musk. I inhaled deeply as I ducked under the hanging canvas flap. He knew I was there at once, and I soon saw why he was angry. I'd be angry too if someone locked me in a cage made of thick iron bars.

I moved closer to the little cage and the golden form inside it, swimming against the current of sound, not knowing what to do or say but desperately needing to see him better. When I'd pushed close enough, the noise stopped.

"Hello," I said, in the ringing quiet, feeling foolish at the simple word but unable to think of anything else. Slumped on the raised wooden platform now and just about my size, the boy only looked at me.

After a minute of that hot, unfriendly gaze, I started to fidget.

"I said 'hello'," I repeated. "Why won't you speak to me?"

"Because I can't talk," he said belligerently, speaking perfectly good English.

I shook my head at that. "Why not?" I said finally.

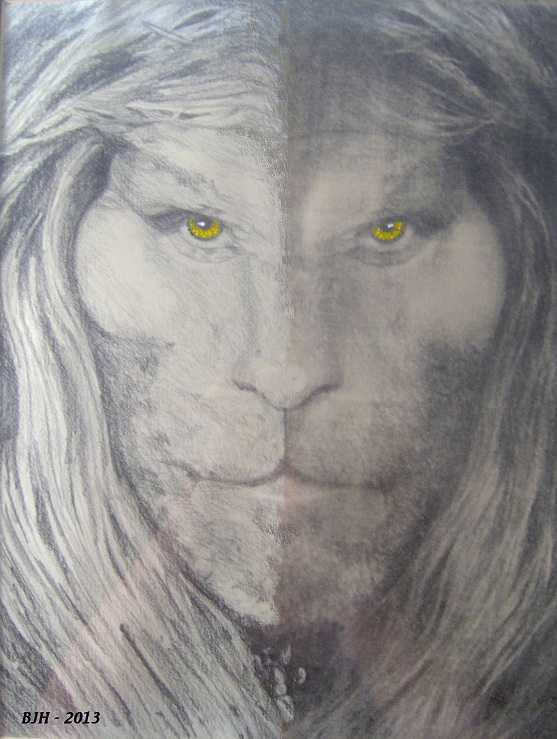

He looked down. "I don't know." Then he met my eyes. His were yellow, like the piece of amber Hattie keeps in the drawer along with her other magic stuff. I knew from the little mirror on the wall at home that mine were green.

"What are you looking at?" he challenged, a sharpness replacing the flat tone of his voice.

I thought that was kind of a stupid question. "I'm looking at you. Can't you tell?"

"Well, stop it! I already know I'm a freak… and I don't like to be stared at!" The angry growl had come back into his voice.

By way of answer, I took off my floppy hat, the one Papa makes me wear out in public so people won't see my ears so easily, or the short hair on my face.

"It's okay," I said, "I'm a freak too." That word didn't mean anything bad to me; it just meant different. Lots of the people who lived and worked at our carnival were different. Like me, they spent some time in the "special attractions" tent after the big show so the marks could pay to look at them. Joe the alligator man said it was easy money. How bad could that be?

The boy moved closer to the bars, gliding along, using his hands almost like another pair of feet. The cage was built low, and I guessed he couldn't stand up in it. He crouched down, as close as he could get to me.

Then we both stared… at each other.

The hair on my head was uncut but only a little longer than the short fur on my face, while his had grown down to his shoulders, dark brown and full of curls. I touched my nose. His looked flatter than mine felt, and his lips were thin, turning downward at the corners and showing flashes of teeth that looked as sharp as mine, or maybe even sharper. He wasn't wearing anything, no clothes at all, not even pants like Pa and Papa always insisted on, but the way he was crouched I couldn't tell what he might have to hide. Except….

"You have a tail!" My mouth fell open. Some of the marks who came to look at me called me a tiger boy. I didn't mind. I'd seen pictures of tigers in one of Papa's books, and they were big and strong and beautiful. But unlike the tigers in the pictures, I'd never had a tail. Since it couldn't be, I tried not to think about it, but I had always kind of wanted one. Imagine being able to swish that powerful furry whip however you wanted, or just wrapping your toes up with it on a cold night.

"So what!" he said, like I'd slapped him. His brown-tipped tail moved, restless, back and forth, but when he saw me staring he held it still behind him.

"So I've always wanted a tail, that's what!" I said, feeling a little heat myself, and then remembering to be sorry and not angry because, after all, he was locked in that cage.

His eyes widened, and I saw him look toward my butt, round and ordinary in my britches. There were little gold streaks in the yellow around the dark slits of his eyes, and touches of brown too. His ears were large and round to my pointy ones. The curly brown hair on his head spread over his shoulders and onto his bare chest. It looked soft. Below those curls was the same kind of short gold fur as on his face. It didn't get brown and long again until it reached the shadowed place between his legs. There were a few brown curls around his ankles too, and his fingernails were thick and blunt and a lot like my own, except his were longer - probably because Papa made me file mine.

He was beautiful. Without thinking, I took a step closer.

His long arm moving like lightning, the lion boy grabbed my shirt front and yanked until I was face to face with him, only the cold metal bars holding us apart. My heart jumped, and I reached up to push him away.

The curls on his chest felt surprisingly soft, and I forgot to push him and started touching, petting, like I would Hattie's old gray cat. After a second or two, his angry jaws unclenched and he let go my shirt. When I didn't stop or move away, he used his thumb to touch my cheek, just a little and real soft, like he was afraid he might hurt me.

His breath smelled hot and good, like fresh meat. I took a deep breath, and then his nostrils flared.

"You smell like me." He said it softly, eyes on my face.

I nodded. That's why his smell was familiar. It was like my bed at home, and the old stuffed bear I'd slept with for so many years. "I do," I agreed. One corner of his mouth turned up, showing ivory teeth. His eyes sparkled. He was smiling!

"We have to get you out of there." It came to me without thinking - the most obvious thing in the world - but his face went blank and he stopped touching me.

"He'll never let me go." His voice was hollow, like wind through dead leaves.

"I'll make him!" I said, wanting to see him smile again, but he turned his back.

"Go away. I wish you'd never come here." I felt his words like a thorn piercing the raw red flesh of my heart.

Faint and far away I heard Papa calling me, his voice getting louder and higher with each repeat of my name. I knew that tone and that I'd better answer him quick if I knew what was good for me. But how could I leave this beautiful boy? I knew I had to answer Papa and… maybe he could help! I stepped back a little, jamming my almost-forgotten hat back over my ears, like Papa always reminded me.

"My name's Tommy. What's your name?" I asked softly, wanting at least that much to take away with me.

He shrugged. "Don't have one." His voice had gone dull again, and he hung his head.

I'd been Tommy for eleven years, since before I could remember. Could a person really not have a name? How was that possible? I stared at his golden brown head, remembering that the curls were as soft as they looked.

How must it feel if no one called you by a name? Would you think you weren't a person at all? My thoughts turned to the camp dogs, Rover, Blue, and Copper, and Hattie's old cat, Mittens. I was outraged. Even animals had names.

I had a sudden memory of stars in the summer sky and Pa pointing out the bright constellation that must have been high on the night I was born.

"I'll call you Leo, then," I said. I turned from his sudden openmouthed gaze and ran back to find Papa.

Papa let out a long sigh when I ran up to him. He was busy talking to a fat man in a shiny gray suit, but he grabbed my hand and pulled me close, putting his other arm around me. I was shaking, and the hug felt good. Papa's voice was quiet but intense, like it gets when he really cares about something.

"I heard the cry with my own ears, Mr. Dawson. I'd like to know what made it."

The gray man scratched his head.

"Well, we've had some new arrivals today, perhaps one of them…."

"Yes, sir. My main concern is that it sounded almost like a human child in pain."

The man, (Mr. Dawson?) raised a palm. "Oh no, Mr. Stone, I assure you that it can be nothing like that. Undoubtedly you heard the call of some exotic animal or bird. My men and I will sort it out. There's no need for you to concern yourself…"

The crowd flowed close around us. Some of them must have heard too, but they'd gone back to laughing and enjoying their day like nothing at all had happened.

Papa broke in. "I must insist on seeing this animal, or whatever it might be, Mr. Dawson. And, as a representative of the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, it is my personal responsibility to see that any animal is being treated humanely."

I wanted badly to tell Papa that it wasn't an animal at all, but every time I tugged at his jacket or even moved very much, his hand gripped mine tighter. Sometimes it even hurt a little, though I'd never let on. I knew it meant that Papa needed me to be quiet right now. So I waited, thinking about Leo and trying to believe that Papa would make everything come out right in the end.

At last the gray man threw up his hands. "Very well, if you're so stubborn-set on it, then you go on and search for the animal. Feel free to poke around, but don't expect folks to welcome you. Animals may have rights, but my people have rights too!"

Papa nodded. "Thank you, Mr. Dawson. I'll be sure and tell everyone that you gave your permission for my intrusion."

Mr. Dawson gave a snort, and Papa turned away, pulling me along. When he had led me into the space between two tents, he squatted down to my size and took hold of my arms, shaking me a little.

"Damn it, Tommy! You gave me a fright back there! I was forever calling you! Where were you, young man?" Papa never swore unless he was really upset, but I couldn't worry about that right now. At last I had a chance to tell him about Leo!

"I saw him, Papa! I saw the boy!"

"What boy?" He stopped. "You mean it was a boy who made that sound?"

"Yes, sir. His name is Leo, except it wasn't his name at first because he didn't have one but that's his name now and Papa…." I took in a deep breath. "They have him in a cage!" I felt like I'd been running.

"A boy in a cage, Tommy? Where is he? Can you take me to him?"

I grabbed hold of Papa's hand and pulled him, fast as I could, through the maze of tents and trailers, following my memory and my nose.

The area had been deserted before, but now we stopped short. A tall, dark man dressed in dirty khaki pants and shirt stood in front of the entrance to the small tent, arms crossed over his thick chest. A braided rawhide whip was coiled at his waist. When he spoke, he had an accent to his words that I'd never heard before.

"I am Ivanov. What do you wish of me?" His face was shiny with sweat, his beard and mustache thin and greasy, and his eyes were blank, like a snake's. I didn't like him.

"My son tells me that you have an animal in this tent - in a cage." Papa's voice was low, just this side of menace.

"And if I do?" The man looked Papa up and down with a sneer. He never even spared a glance for me.

"We wish to see the animal. Mr. Dawson gave us permission to look around."

The man's eyes narrowed, crafty. "Ah, but I do not yet work for Mr. Dawson, but only for myself. What will you give me to see him?"

I took in a deep breath. I could smell that Leo was still inside the tent, but he was being awfully quiet now.

Papa smiled at the man, but not like he was happy. "I am glad to pay to see him, Mr. Ivanov. Will a dollar do?" Papa handed the man a large silver coin, which quickly disappeared into his pants pocket.

The man's lip curled. "You are a fool to pay so much, but I will not argue. Come and see my fierce beast, then."

I couldn't stand it. I had to speak. "He isn't either a beast. His name is Leo, and he's my friend!"

The man looked at me as though he'd just noticed I was there. Papa pushed me behind him. "My son tells me he talked with the boy in the cage, sir."

The man snorted. "Your son is mistaken. This beast belongs to me, and I should know him. He is but an animal. He cannot talk."

I wanted to protest again, but Papa gave me a little shake, and I said nothing more. Ivanov seemed to lock eyes with Papa for a minute, and then he pulled back the tent flap with a flourish, going in ahead of us. I caught a bare glimpse of Leo, curled into a little ball in the very back of the small cage, and then Ivanov took the whip from his belt and snapped it in the air, loud as a crack of thunder.

That golden form uncoiled and threw itself at the cage bars, a pinwheel of snarling, spitting anger. He was making that sound again, that howl that raised the hair on my spine and made me want to howl along with him.

Ivanov raised the whip again, and Papa ran forward, jerking it out of his hand. The man began cursing Papa and raised his fists. I'd seen Papa use a whip many times, snapping it overhead when he started the big show. Now he gave Ivanov a shove, and, quick as lightning, Papa's arm came up and I saw the knotted tip of the lash curl round the man's back. Ivanov cried out and sought to grab the whip's end, but Papa jerked it away. "How do you like it?" he asked, voice tight with anger. Ivanov sprang toward him.

I forced my eyes back to Leo, but his frenzy seemed to have doubled at seeing his tormentor at the other end of the whip. I called out to him, over the angry shouts and scuffling, but I guessed Leo couldn't hear me over his own growls and shrieks.

Just then the tent flap was tossed aside and the space was filled with men. The first threw me out of the tent to sprawl in the dirt, and before I could get to my feet, four of them came back out with Papa and Ivanov both held tight and struggling. Ivanov was yelling words I'd never heard before, but they still sounded like curses. Papa only said one thing, "Tommy!" as they dragged him away, and I followed blindly, Papa my only anchor in a topsy-turvy world. Behind us, the cry of heart-deep anger and pain went on and on.

Papa sat on a wooden chair inside a small tent, and I sat on the ground beside him, both arms clutched around his leg. Once in a while he patted my shoulder, but his attention was for Mr. Dawson, seated behind a desk across from us. "Sir, I must ask again that you let us go."

Mr. Dawson shook his head. "I'm sorry, Mr. Stone, but such a disturbance as you've made is for the law to handle. We'll have to wait till they arrive and deal with it." Mr. Dawson looked up, and the big roustabouts by the entrance shifted their feet, maybe uncomfortable with guarding us.

"I have no problem with your calling in the police, Mr. Dawson. My only concern is that Mr. Ivanov be brought to justice."

Mr. Dawson looked even more unhappy. "That's no concern of mine, sir. He only arrived this morning, asking for employment. I had not hired him on, so his actions are none of my responsibility."

Papa was silent, but his look of disgust was plain. Mr. Dawson spoke up: "Don't think to moralize with me, sir! I have enough to worry about right here in my own show! I can't be responsible for the whole damned world!"

Again, Papa said nothing, just reached out to me. I held his hand.

We had sat for a few more hot, quiet minutes when there was a commotion at the entrance and another of the roustabouts pushed his way in. "Mr. Dawson, he's gone!"

Mr. Dawson stood up, but Papa was faster. "Ivanov?" he asked.

The roustabout looked toward Mr. Dawson, but then he answered. "Yes, sir. We let him go outside the tent because he said he had to… you know, and it was only a minute, but when we went to look for him he was gone! His whole rig's gone now too!" The man's face was pale, and he was sweating.

Papa turned back to Mr. Dawson. "Will you hold me even now?" he challenged.

Mr. Dawson looked down at the papers on his desk. "Go on. I've got better things to do with my time. I wash my hands of the whole affair." I thought Mr. Dawson looked relieved.

Without another word, Papa took my hand, and the roustabouts parted before us.

The law arrived just as we were climbing into our Model A. Sheriff Pickerel didn't seem too impressed with our story, but he did look around and confirm what we already knew - Ivanov was gone, taking Leo with him. He asked Mr. Dawson and the roustabouts a few questions, but mostly he looked bored. I could tell Papa was angry, but he did his best not to lose patience with the sheriff. Some people didn't trust any kind of carnival folk at all, and it seemed that Sheriff Pickerel was one of them. What happened between two of "those people" wasn't of much concern to him.

"He's gone, all right. Doubt if we'll ever find him now," he said without interest. It looked to me as though Papa might choke when he thanked the sheriff for his trouble.

We drove slowly into town. It was almost dusk, much later than we had intended to stay, and Pa would be worrying about us. But Papa went first to the telegraph office and sent wires to all his friends in other shows so they'd be on the lookout for Ivanov. I knew it was the best we could do, but part of me wanted to run off down the road, searching under every rock and tree for Leo.

Papa held me on his lap as he drove, curled under his chin, like he hadn't done since I was a little kid. It helped some, as did telling Pa and our other friends about all that had happened when we got back home.

As days went by and then became weeks and finally months with no word, I began to feel numb. Maybe we'd never find Leo, but I knew I, for one, would never stop looking.

I didn't know if Pa and Papa understood just how much I wanted to find the lion boy.

For the first time in my life, I'd met someone who was like me, and I couldn't just let him go.

* * *

Timothy Lacey had never fit in. Although the town did not formally exclude him from the worship services which made up an important part of the Laceyville community's social life, the suspicious glances he received when he appeared in the little wooden church made him reluctant to attend often. Everyone seemed convinced that being born with a harelip, no matter how slight, denoted at least the tendency toward sin, if it was not an outright mark of Satan himself.

Tim tried not to worry too much about such things. He felt neither cursed nor particularly blessed, his young mother having been called to glory a month before his first birthday and his much older father having sent him down the road to be raised by his grandmother.

The old lady, though kinder to Tim than most folks thought proper, lived only long enough to see him through childhood, and her farm passed to him, poor place that it was, with no one caring to dispute his claim, just after his sixteenth birthday.

Timothy missed his Gran, but he was glad to keep the old homestead. Its one claim to goodness was the apple orchard where Gran had taught Timothy the joys of nurturing God's gifts from the earth.

In spite of his deformity, which caused him only a slight tendency to lisp, he was well grown and strong. The other lads his age, whom he often saw when he came to town to trade apples and cider from that year's crop, were married or courting, but no offers had come to him from the preacher, Brother Grovner, who often arranged the matches between families, and Tim knew that any overtures he might make about a likely young girl would be refused.

Tim did his best not to dwell on that fact, and he kept his face turned away and the brim of his hat pulled low when he chanced to meet a girl - or a female of any age - swaddled in their long dresses and aprons, poke bonnets hiding their faces.

He'd grown quite used to his solitude, which he tried not to think of as loneliness, and Tim was surprised, one evening, to see a young man coming down the dirt track to his cabin, especially since the boy was leading a pair of horses. Even in the dim light, he recognized the lad as the oldest son of his father's second wife, only two years or so younger than himself. Though the woman never let her children consort with him, they were still his half brothers, and Tim had sometimes seen the boy as both of them hunted in the hills surrounding the town.

Tim brought out a lantern. "Hello," he said, as the young man tied the horses to the porch rail. "Will you join me in a glass of cider?"

The boy, Ethan was his name, Tim knew, looked around uneasily, then nodded and sat on the porch step. "Thankee," he said.

Tim poured for them both, and they quietly sipped, keeping several feet of distance between them, seemingly by mutual consent. Finally, Ethan spoke. "Pa's dead," he said unemotionally. "Fell from the combine in the oat field yesterday. Hit his head and never woke up."

Tim sipped the hard cider, feeling its warmth burn his throat. "The family going to be all right without him?" he asked. "'Cause I could help…" Even though he knew what his father's wife thought of him, her children were still his flesh and blood.

"We'll be a'right," the youngster interrupted. "Ma's brother and his wife will help out. They'll be movin' in with us come next week."

And why not, Tim thought. His father's farm was one of the largest and richest in the valley. He nodded, then glanced at the horses, both standing quietly.

Ethan spoke up. "This is the team was pullin' the combine. Pa always said they was no good, too light for farm work. Ma says you won't mind that since you got no crops to till, so these be your share of Pa's property."

Tim nodded again, stifling a sigh. Bad luck horses for a bad luck man. He supposed it was only right. He wasn't likely to receive any other legacy.

Ethan put down his tin cup. "Thanks for the cider. I'll be goin' now."

Tim watched the boy, well formed and handsome of face, as he trudged up the road and back to his own farm - a half mile and another lifetime down the road. Only then did he go over to the horses, a nice pair of matched buckskins, even if their buff colored coats were shaggy and their dark manes and tails tangled with burrs. Untying their halter ropes, he led them to the old stable where he kept the cider press.

Having the horses was almost like real company, Tim thought. He'd never had a cat or dog, and since Gran passed he had often felt like a hermit. Unlike the town folk, the horses seemed to like him, meeting him at the pasture gate of a morning, nosing his pockets for the windfall apples he brought them. He judged them six years old, a gelding and a mare, fifteen hands tall, and when he'd curried the thick coats and combed out their manes and tails, he'd never seen a finer pair hooked to a buggy or wagon, though his pa had been right in thinking they were too light for farm work. Perhaps the old man had taken them in trade and tried to find some use for them.

Tim himself had little need for the horses. He kept a pair of mules for hauling wagonloads of apples into town, and they were quite enough. But after a time, Tim grew fond of the gentle and beautiful animals, and he found that he didn't want to part with them, even though a traveling gypsy trader offered him a good price.

The routine of caring for the animals gave him a reason to rise in the morning. The mules he left to roam the rough pasture, savvy enough to stay out of trouble or defend themselves against most any of the small predators found in the hills, but the horses he kept in the barn and the small paddock, leading them down to the creek for water morning and evening, and he felt a spark of joy that some other living thing depended on him for its care.

There was no joy in looking across the creek, though. Just far enough back from the water for their cabin to be out of sight, lived the son of his mother's brother.

Caleb's wife had given him two healthy sons, but that hadn't sweetened Caleb's temper toward her. Most every night, Tim would hear his cousin's voice raised in anger, and sometimes he caught the high and pleading notes of fear and sorrow from the woman. Tim had seen her in town, a shy, thin wraith of a girl, no more than the glimpse of tight lips and large dark eyes visible under the brim of her bonnet.

Once, when Gran was still alive and Tim only a child himself, he had ventured to speak to his cousin's wife. He still bore the scar across his cheek where the whip handle in Caleb's heavy fist had cut it open. He'd cuffed the woman too, when she'd dared to say, "But, Caleb, he's only a boy."

And Caleb had responded, "I told you not to look at him. You want to wish that devil's mark onto our child? Do as you're told, woman!"

Tonight the yells were particularly loud, carrying well across the water. "Down on your knees, woman," Tim heard Caleb screech. "And pray the Lord have mercy on you, because you'll have none from me."

Tim knew there was nothing he could do. By the code his people lived by, Caleb was well within his rights as a husband. Tim turned away as his eyes filled with tears.

The main problem with raising apples, Tim thought, was it left him with too much time on his hands. He read his Bible, the only book Gran had kept in the house, but he read other books too, that he had got from traders from outside the valley. No one looked with favor on anyone who traded outside, but many did on the quiet, when they needed money, and Tim didn't see how the town folks could possibly think any less of him than they did already, whatever he might do.

One book, his favorite, was almost worn out from use. In it were color pictures of a circus, tall tents and happy people in bright clothing, strange animals with spots or stripes or long unlikely snouts, and best of all, beautiful horses. One page showed a man in exotic dress, not riding, but standing tall on the back of a horse as it trotted around the ring, even jumping through a large hoop. He'd tried doing such tricks on the backs of his stolid mules, with less than satisfying results, but now that he had a pair of horses fine enough to be seen in any circus, he decided to try again. Would the horses stand for it? There was only one way to find out.

It took some doing to come up with the right combination of footwear and saddle, but the first time Tim stood on the mare's back as she calmly walked along, he felt brave - strong, as though he could do anything. Working at it every day, it didn't take them long to learn together. Soon he could stand on a horse's back while it trotted, jump off safely, ride backward, and even hang off the saddle like a wild Indian from the old west. Unbeknownst to Tim, his new ways put a spring in his step and a smile on his face.

Now the townspeople looked at him even more suspiciously, and Tim began to wonder if it wasn't time to strike out on his own. Surely someone, somewhere, would appreciate what he had learned. There had to be a place where he could fit in and be accepted.

As summer became fall, Tim built a wooden cover for his wagon, making it into a small house on wheels, modeled after the pictures of circus wagons in his book. Circuses or their smaller cousins, carnivals, were never welcome in Laceyville. While Tim relished the thought of new people and places, the rest of his fellows seemed content with the monotonous, drab existence they had inherited from their forbears. That was the biggest thing that separated him from his relatives in the valley, he decided. He wasn't afraid of change.

But could he really go away and never come back? Leave behind the only home he had ever known, the beautiful orchard and the memories of his Gran?

The moon was new that night, the sky grown almost too dark for him to find the way to the stream. But the horses remembered the well-worn path, and he climbed on the mare's back, lolling lazily as she and the gelding wended their way through the tall grass.

They had reached the creek. Tim could hear the clear music of the water, but the horses shied suddenly, the mare rearing and almost dumping him on the ground. He slid down, his rifle finding its way into his hands. Could it be a cougar, come down from the hills? He tossed the lead ropes across the horses' necks to give them freedom to flee, and he approached the water with caution. Starlight was not sufficient for sight, so he stretched his other senses as he crept along. At first there was a small splash-perhaps a jumping frog or fish-but then came the smell, the rich, metallic, unmistakable scent of blood.

On the other side of the water, perhaps twenty feet upstream, a voice was raised in a curse. Heavy boots clomped away, and Tim waited while the retreating voice faded to mutters and then was gone.

Feeling his way to the muddy bank, he all but squealed when his hand found a wet cloth bundle snagged on a log. Something was inside the bundle, and it moved. All at once, the mare appeared beside him, ghostlike, and her soft nose touched the cloth inquiringly. Comforted by her presence, his knife cut through the tangles, and he lifted the soggy bundle in his arms. When the horses had got their drinks, he carried it carefully as he walked beside them.

In the lantern's light, the baby laid on Tim's kitchen table was tiny, not that he'd seen a newborn close up before. Its miniature arms and legs seemed perfectly formed, the testes and small penis mute evidence of its sex, but the child's lip was split, almost like his own, and there was a downiness, like a new-hatched chick, covering the little body from head to toe, not to mention the thin curve of a tail at its backside. Suddenly, Tim knew from whence it had come. There would be no rejoicing at this birth in church come Sunday. Caleb had intended to make certain that his newest son never saw the light of day.

Tim had never imagined himself as a father, but he knew he could not let this baby die, nor could he keep it with him here for long, where its cries might lead to discovery. God, not the harsh God Brother Grovner preached, but the gentle God Tim hoped was real, had sent him a sign. It was time to leave this valley, and with him would go the infant, his new son.

He cleaned away the blood with a cloth and warm water and swaddled the baby in a dish towel and a blanket torn from his bed. The slit-like pupils in the yellow eyes seemed to watch him, and the little mouth opened eagerly for a cloth dipped in fresh goat's milk, pink tongue licking up every drop.

"What shall we call you?" he asked the tiny boy. "You need a name, my son."

Tim had never met his grandfather, Gran's husband, but he knew how much the old woman had always missed him. "I think we'll call you Richard," Tim said, smiling into the little face. "Richard Timothy Lacey." He smiled again at his own indulgence. Though the baby was different, he couldn't imagine his Gran not loving him, just the way she had loved Tim.

It was easier than he'd thought to find a carnival. In the first large town he came to, the sheriff said a show arrived about this time every year, and they didn't mind if he pitched camp on the fairgrounds to wait for it. The few who noticed his harelip asked no questions, just nodded in sympathy. Still, Tim kept baby Richard safely in the wagon. The goat continued to provide ample milk, though the first project on Tim's agenda while he waited was to build on a little porch for the animal, so it might ride outside the wagon.

James Forsythe seemed impressed by Tim's abilities with the horses. Tim did his best tricks for him, leaping from one broad back to the other while the horses ran and doing a handstand over the mare's neck, his toes pointed at the sky. By the time he had completed his routine, others of the company had come to applaud, which Tim found left him quite flustered.

"Report to the wardrobe mistress," his new boss told him, hooking both thumbs behind his bright red suspenders. "The only thing that won't do is that drab outfit, but I'm sure we can find something for you by tomorrow's performance." The smiling man thrust out a hand. "Welcome to the show!"

Tim, who had always made a point of carefully shaving every morning, cast an extra glance at the boss's thick brown mustache. Perhaps, if he let his own mustache grow, it might even cover his deformity. Pity something so simple wasn't possible for his baby son.

The dark-haired woman was striking. Almost as tall as Tim, she was stoutly built, not a delicate flower like the women so favored in Laceyville. She wore a man's shirt and trousers too, showing off her small waist and generous hips. Tim liked her at once, especially when she boldly stuck out her hand. Her grip was firm.

"I am Sasha," she said, "Sasha Ivanova, and I work with horses too." Her dark chin-length hair swirled across a pale cheek as she turned, glancing at the buckskins. "But not like these. What kind horses are these?"

Tim had to admit he didn't know their breed, though they looked a bit like pictures he had seen of Arabians, with their small heads and slender legs.

"My horses very different," Sasha continued, "and you do not ride them. Oh, no. My horses, they dance!"

Tim knew his mouth must have gaped, but Sasha took no notice. She grabbed one of his hands again, exerting a strong pull. "Come," she said. "We will go and see my horses now."

But Tim resisted. "I, uh, I would like to see them, but I can't leave, uh…" Richard chose that moment to let out a mewling cry, and Tim had no choice but to go to him. He was surprised to find Sasha there behind him.

"A baby, yes?" she asked. "Let me see him."

Sasha's horses were different. They were large, some a dappled gray but many pure white, their intelligent, liquid eyes and huge hooves the only dark things about them. "From the old country," she explained. "Once war horses, now circus dancers." She laughed, her red mouth wide and generous, her blue eyes sparkling.

From the first moment, Timothy was dazzled, more so because Sasha cuddled and cooed to Richard as to any baby. "Sweet little furry one," she said, "so pretty and soft," as she tucked the specially folded diaper around his tail.

Little time went by before Sasha was in Tim's bed, brushing aside his awkward inexperience with a "For everyone is first time, yes?" before he could really be embarrassed.

With his act going better than Tim had ever imagined, thanks to Sasha's suggestions on showmanship, it wasn't long before there was talk of marriage. Afterward, Tim was never sure exactly who popped the question.

Sasha was not only beautiful but bold and full of ideas. "We combine the acts, yes? You will teach me to dance on horseback, and then we will all dance-horses, you, and me!"

And that's just what they did. The wardrobe mistress continued to watch out for Richard, as she had done from their first performance, and now both Sasha and Timothy were in the ring at once, leaping and waltzing on the backs of beautiful and graceful animals who stopped and turned to waltz a step or two on their own. It wasn't long before James Forsythe had to raise their salaries, or lose them to the other companies who came to woo them away.

No other children arrived, but Richard was a delight. Forsythe's show had no "special attractions" tent, nor would Tim have been in favor of exhibiting Richard as a "freak," but there was talk of adding him to the act when he was old enough. Already he rode the gentle horses, long accustomed to his scent.

Timothy could not remember ever being so happy.

Richard was four when Sasha made an announcement one evening.

"I have telegram from my brother, Vasily," she said. "He is in need of job, as usual. Pah. Forsythe will not hire him. He has big cats already, no need for Vasily's leopards. Vasily is no good with cats. I tell him long ago to find job in town, but no, he believes circus is in his blood. He will not listen."

Tim shook his head, wondering what it must be like to have a brother or sister. "Perhaps we can send him some money, help him out?" he said kindly.

Sasha smiled, kissed his cheek. "You are good man, my Timofei, but he already is on way here, will meet us in next town. The boss-man, he say he can give him work as roustabout, make enough money to move on with animals." Sasha smiled and bounced little Richard on her knee. "He grows big, yes? See those teeth!" She laughed.

Richard had been eating grown-up food for some time. He loved meat, would eat vegetables if coaxed, and hardly ever asked for milk anymore. His downy baby fur had matured into an allover golden coat, the hair on his head longer and darker, and he'd been talking since he was nine months old. "Smart boy, this one," Sasha said fondly.

Richard patted her cheek with one small velvet-furred hand, his nose lifting to sniff the air. "Mama," he said, tail curling around her waist. "I'm hungry."

Sasha cuddled him close. "Soon will be meat, little one."

Vasily Ivanov's handshake was crushing. "Pleased to meet you," the large man intoned while looking Tim up and down. Tim used his painfully wrung hand to brush at his mustache, glad his deformity was not on immediate view. Somehow, he did not think this man judged as generously as did his sister. Still, in the close quarters of the camp, it was difficult to keep one's business private, and it was not long before Vasily met Richard.

"Ah!" he exclaimed when Sasha presented him. "The little leopard boy."

"We think he looks more like a lion," Tim said defensively, wanting to scoop Richard up and hide him away.

"Leopard-lion-all big cats, yes?" said Ivanov, laughing. "Come here, little cub, and see your uncle Vasily." He reached out both thick, hairy arms toward the little boy.

Richard bit his thumb and retreated behind the stove.

The big man turned away, blood dripping from the wound, his face an angry mask. His voice, as he left the tent, was raised in words Tim didn't understand, but Sasha frowned and shook her head.

Still, he was back in minutes, thumb wrapped in a handkerchief, offering Richard what looked like the large leg bone of a goat. The child took it warily. "You see," Vasily proclaimed loudly. "He only needs little time to get used to his uncle, yes?"

Richard took the bone to the corner of the tent. Later, Tim found it abandoned there, un-chewed.

That night, safely in bed in their own wagon, Sasha yawned in Tim's arms. "My brother," she said sleepily, "always the quick temper." Her eyes soon closed, but Tim lay awake for a long while.

Vasily's leopards, two females and a male, looked bad when Timothy finally saw them. Vasily had been hounding the show's doctor, who also cared for the animals, for tonics to "strengthen" them, but Tim thought it would take more than that. The male limped around the cage, restless but unsteady, and the females curled in opposite corners, rarely moving even when raw meat was tossed inside. When Tim dared to broach his concerns, Vasily clapped him hard on the back. "They are but animals. Meat is all they need." The leopard closest to where they stood dragged herself to her feet and moved slowly away. "That, and the touch of the whip, yes?" Ivanov said, patting the coil of rawhide he kept strapped to his belt and grinning.

Tim said nothing, but he noticed that Richard tended to disappear when Vasily came in. "He smells bad," the child told Timothy one night at bedtime. "Like sick things."

Tim hugged the boy. Though he tried not to worry, Vasily didn't smell so good to him, either. But he's Sasha's brother, he told himself. He's family.

Neither Timothy nor Sasha worried much when Richard didn't come in one day at dusk. They both knew his night vision was far better than theirs. But as the hours passed and suppertime came, Tim's heart began to pound.

Vasily appeared, as he usually did when food was ready, and he reassured them that Richard would soon come back. "He is only hiding from you, playing a game, perhaps. Or out stalking dinner for himself, like a good kitty-cat. He will return with a mouse, yes?" Vasily laughed heartily, but Tim felt cold all over.

"Did you see the little one this night?" Sasha asked her brother. "I know he speaks to your leopards sometimes, when you are not close by." Her eyes narrowed as Vasily flattened both large palms on his chest.

"I? I have not seen the little one since last night-here, at supper." His face was a picture of puzzlement. "Surely he will return soon to his mama and papa. If not tonight, then by tomorrow."

Tim went out to search later, not telling Sasha because he did not want her to worry. The field in which they camped backed up to a stand of thick trees. The lantern's light showed vines and creepers as well as leafy branches, and Tim thought anything might hide in the tangle under the tall trunks.

In the morning, Vasily was the first to volunteer for a search party, joining every carnie that could be spared. But on the third day, he came to Sasha. "I have job offer in next state. I must leave, dear sister. But you will soon find the little stray, I know. Tomorrow, the sheriff, he tells me they will bring special dogs to hunt. Then you will have no worries." He smiled at Tim and shook his hand; then he was in his wagon and gone before noon.

But the sheriff's dogs found nothing. Even after sniffing Richard's pillow and heading off into the woods, barking like mad things, they returned, puzzled and whining. The sheriff scratched his head. "Thought for sure they was onto something, but I guess not. They led us a merry chase through those briars, but we only found some broken branches and grass pressed down. Likely some animal spent the night there. I'm truly sorry, Mrs. Lacey," he said, his hat held in his hand, "but I'm sure he'll turn up eventually."

Sasha burst into tears, and Tim held her and squeezed shut his burning eyes.

Tim and Sasha stayed behind when the carnival moved on, but days passed and Richard did not return, and they were sure they had combed every nearby bush and tree, more than once. Richard was gone, yet no trace had been found. Where could he be? Could someone have taken him?

During the long, dark nights, they clung to each other, neither daring to say what was on their minds: Vasily.

* * *

It had been so long, I figured I would never again hear anything about Leo. Then one day Pa told me Papa wanted me in the big tent.

"Here's Tommy now," Papa said when I walked in. "Son, come over and meet Mr. and Mrs. Lacey."

The man and woman were maybe Pa and Papa's age, him with brown hair and a thick mustache and her hair shiny and black like Papa's. They stared at me so hard it kind of made me uncomfortable, and I walked up slowly. Then they looked at each other and shook their heads, and some kind of tension went out of them, like they were too tired to sit up straight any more.

"Hello, Tommy," the man said to me. "Your papa has been telling us about you."

I nodded and shook his hand, and the lady's too, when she offered it, then I sat down next to Papa and listened.

"You need to understand that my wife and I," the man said, "may not want to stay with your show for long. We've been with a lot of shows, traveled all over the country. I don't know if you've heard of us?"

Then it suddenly clicked. They must be those Laceys, the ones with the beautiful white horses. I was only thirteen, but sometimes Papa let me help out with bookings and travel arrangements. Said it was good experience for me. He took me along to meet the owners of other carnivals too, sometimes, and I always read in the papers what it said about our competition. It seemed to me that the Laceys and their dancing horses had been with almost every big show I'd ever heard of.

"Of course," Papa said, "and we'd be happy to have an act of your caliber with Caldwell's Wonders, but can you tell me why you don't stay long with one show?"

The two of them looked at each other again, and then he said, "We're looking for our son."

It looked like we'd be talking a while, and Papa had me run and get lemonade for everyone. When I came back with the cups and jug, Mr. Lacey was saying, "We haven't heard from Sasha's brother in years, but we figure he must be with some show somewhere. And if he did take him, then…"

Papa nodded and smiled at me as I poured out the drinks and handed them around. "May I ask why you were so eager to see Tommy?"

This time the lady spoke. "We were told about your Tommy. He looks just as our friends described him, not much at all like our Richard, but it is the closest we have come in years, and we hoped…" She stopped, pressing her lips together.

Papa glanced at me. "Can you describe your son?"

"Of course," Mr. Lacey said. "He would be fourteen now. His fur is more golden than Tommy's, and he has dark hair on his head and a…"

I stood up, spilling my lemonade. "A long tail!" I said, interrupting. Then I almost shouted, "Leo!"

There was a lot of confusion after that. It took hours of talk to settle it all, during which we fed the Laceys dinner and found a place for them to make camp.

Everyone in our circle had heard my story of the lion boy, but me and Papa told it again, and we all had to hear the Laceys' story too. Mrs. Lacey shook when Papa told the part about Ivanov threatening Leo with the whip. "How could he do such a thing?" she kept saying. "My own brother. Oh, Tim, I am so sorry." And Mr. Lacey kept shushing her.

"It's not your fault, my dearest, and it means Richard was alive then," he said. "God willing, he still is."

Two years, though, I thought to myself. And he'd been with that man since he was only four? How had he lasted that long, and could he still be alive after another two years? Alive… I swallowed hard… and sane?

So the Laceys stayed on with our carnival. Pa and Papa had contacts with many other shows, and they had contacts, and they all promised to let us know if Mrs. Lacey's brother came to them for work. Mrs. Lacey said she had a good feeling, knowing that we were all searching together. I think I reminded her of Leo… Richard… because she always went out of her way to speak to me or give me treats. She made the best meatballs.

And their act was wonderful. The way those horses pranced along and the man and woman leaping from one to the other as though they could fly… it made me wish I could cry, sometimes, knowing what sorrow was in their hearts while the audience applauded.

What with traveling and settling in at a new place, it was a week or so before we had time for another talk with the Laceys. Pa and Papa had been talking together a lot, and I figured it was about Richard, but they always walked away when I came around or went to whispers so soft even I couldn't hear. Finally, we all sat down at a makeshift table outside. Papa had done his special fried chicken and gravy, and my mouth had been watering all afternoon. Mrs. Lacey brought a big pan of apples with a crispy topping and lemon sauce for dessert.

The food was too good for talking, but when Pa brought out cups for coffee, Papa started in. "Mr. Larsen (that's Pa) and I have been talking things over, and we wanted to ask you some questions, if that's all right."

Mr. and Mrs. Lacey smiled and nodded and sipped their coffee.

"As a beginning," Papa went on, "where do you hail from, originally?"

"Sasha," Mr. Lacey said, nodding to his wife, "came over from Russia. Isn't that right, sweetheart?"

Mrs. Lacey nodded.

"And I was born in Laceyville." He said the state too, but like Pa said, it doesn't matter.

Papa snapped his fingers. "Aha!" He looked over, and Pa nodded, the firelight making his red hair and beard shine.

The Laceys seemed startled. "Forgive me, sir, but I don't understand…"

Papa held up a hand. "Please, let us explain…."

So my birthday story got told again. How Papa and Pa and the carnival were passing through a town named Laceyville, whose people weren't at all friendly, and how they happened to camp only a few miles farther on, only to find a baby left outside their caravan in the middle of the night. How that baby was me.

Mr. Lacey jumped to his feet. "Caleb? Are you sure the woman who left him said 'Caleb'?"

Pa nodded. "I believe so, yes."

All eyes turned to me. At first I was too busy feeling uncomfortable at the attention, and then it all came together in my head. Papa and Pa got me a year after Leo… Richard… was almost drowned in the creek by Mr. Lacey's cousin, Caleb. The woman who brought me to their caravan said her husband's name was Caleb. That made me and Richard… why, Richard was my brother!

Mrs. Lacey began to cry, and Pa came and sat down next to Papa, putting his arm around him. I guess they both looked a little peaked too. But Mr. Lacey just sat there, his mouth open and his eyes empty. "Caleb and Ivanov," he said finally, voice flat, like he was talking about the weather, "damn them both to hell."

I didn't know quite what to do. I sort of wished I could cry then too, but Papa said I wasn't built for it. Anyway, my throat got tight, and it seemed hard to breathe. If I'd known Leo was my brother, would I have fought harder to set him free? What else could I have done for him?

After a while, Mr. Lacey caught my eye and smiled a little. "You and me are kin, Tommy," he said. I felt Pa give me a shove, and I got up and went over to the Laceys. When I got real close, I just kept moving until they each reached out an arm and hugged me. Then we all kind of shook together for a while.

That night, I couldn't sleep for thinking, and I thought about him at night, every night, from then on… the lion boy who did have a name of his own, after all.

He was out there somewhere, still alive. I could feel it. My brother.

One night, a few months later, Mrs. Lacey came to our wagon. "I go to town today," she said softly, "to shop. At office there is telegram, sent by sheriff of little town in east." Papa motioned her to a seat, and we all sat down too. "Vasily, my brother, they say he is dead." She opened the folded paper in her hands, as though to read it again. "Killed, they say, by one of his wild animals."

I opened my mouth to speak, but she went on: "It says all animals escape." She looked up. "They search for, with dogs. Find and shoot two leopards." I held my breath. "The sheriff and his people, they are sorry. Can find nothing more."

I looked over, and Mr. Lacey was standing by the door. "What has become of our Richard, Timofei?" she said. "Will we ever know?"

We all sat and talked for a long time, but there was no way to know what had really happened. I don't know about everyone else, but I felt kind of lost. How could we search for him now? If he was alive, and he had to be, he just had to be, then where was he?

But nothing meaningful happened for a long time, even though we asked at every town and every other show and carnival, no matter how small, that we came in contact with. Sometimes we got together with the Laceys to eat a meal and kind of keep our hopes up, but every passing day seemed like one more small step away from Richard.

We usually wintered in Florida, but this year the city of Houston, Texas, had offered to let us put on shows there, staying in one place for the whole season and maybe on into spring. It was further west than we usually traveled, but Papa was always interested in new markets, and most of the other carnies were in favor. So close to a big city, they could do the repairs they needed on their outfits and make some extra money too.

Camping on the outskirts of Houston wasn't all that different from Florida. There were still swamps and snakes and lots of rain, along with plenty of wild country to explore, though I missed the places I was familiar with.

Most nights, it was my habit to finish my work and then head off to hunt. At the beginning of the week, when work was lighter, it wasn't unusual for me to spend a whole night out.

That was fun, just me, doing whatever I wanted. Everyone told me meat should be cooked, but once in a while I liked mine raw. I was always careful to wash any blood off myself afterward, but my dads probably knew anyway, and I compromised with them by bringing back the occasional bird or rabbit for the stew pot.

Today I felt restless, and I could hardly wait until chores were done so I could grab my pack and go off alone.

I had no particular destination in mind, so I just wandered along, following old deer paths and such. I had a good sense of direction, and I never worried about finding my way back. It wasn't long before I had two rabbits. I'd caught both on the run and broke their necks clean, then tied their feet together with a bit of string. It was getting on to dark, and I was thinking about finding a place to bed down when the wind picked up and brought me a new scent. Without even thinking, I slung the rabbits over my shoulder, turned into the wind, and started following it.

A mist rose out of the soggy ground, and I lost sight even before the light was gone, but the scent pulled me, and I kept going, with it getting stronger every step.

Somehow, I knew that scent. I'd smelled it before, though I couldn't think where or when. Heat and musk and… then the moon peeked around a cloud and a figure rose up before me, out of the reeds, a low growl in its throat and a wooden club raised above its head.

I froze in place, and neither of us moved for a minute, but I drew in breath after breath of the familiar scent, and I could hear him doing the same. Then the club fell to the ground with a thump, and I was face to face with golden eyes that captured the last of the light.

A low voice whispered: "Tommy?"

We built a fire, even though it took me a while to convince him it was okay. "There's nobody out here but us, Leo… I mean Richard," I said.

"Richard…." The voice was deeper than I remembered, and hoarse, like he hadn't spoken in a long while. "I haven't heard that name since…."

He sat now, all golden fur and long brown curls and no clothes at all, his legs folded up, his arms hugging his knees, his long, thick tail wrapped over his toes.

"We never stopped looking for you. Your folks have been looking too, ever since he took you away."

"My folks?" His head came up. "Where are they? Are they all right?"

I nodded, putting more wood on the fire and turning the rabbits a little. A bird called, soft and sad, somewhere in the dark. "They're traveling with our show now, Caldwell's Wonders." He looked around, and I pointed over my shoulder. "The camp is that way. About six miles, I'd say."

He nodded and sighed. "I'd like to see them again, Mama and Papa. I never thought I would. At first I just ran and ran, and I always kept to the wild places. But then I knew I'd have to stop after a while." He nodded back at the low outcrop of rock that made a kind of shelter. "When I got here, it seemed a good place to rest."

"How long have you been here?" I asked.

He shrugged, the muscles in his shoulders flowing under the fur. "Maybe a month."

I pinched the rabbit's thigh, then broke off the leg and handed it to him. He looked at the juicy, dripping meat for a moment, then ripped off a bit with his sharp teeth. "Cooked meat," he said quietly. "Tastes pretty good."

Something small scuttled in the bushes, probably scavenging the rabbits' guts from our throw-away pile. Neither of us paid it any attention.

I took a piece of rabbit for myself, but I couldn't wait any longer. "How did you get away?" I blurted. "What happened to Ivanov?"

Bleak eyes, set in an expressionless face, looked up at me. Richard said, "I killed him."

For a minute, I couldn't say anything. Then I swallowed the bite of rabbit and nodded. "Go on."

He leaped to his feet like a jack-in-the-box, crushing the piece of meat in his hand as though he intended to throw it into the fire. "I killed him! What else is there to know? I'm a murderer!"

My heartbeat picked up, but I did my best to stay calm and just kept staring up at him. Finally, he sat back down. "Okay," he said softly.

Richard sighed and continued to chew and swallow as he talked. "From the beginning, he'd dose me with something in my food at night, to make me sleep. I'd wake up and the cage would be clean and we'd be camped someplace new.

"At first, after he took my clothes and put me in one of his leopard cages, I'd cry and cry for Mama and Papa, but he only yelled at me, 'Shut up, stupid beast,' and hit me with a riding crop and, later on, the whip. I never spoke around other people, after the first couple of times, because I knew how badly he'd punish me. It didn't matter anyway; people didn't listen. They only wanted to see the 'beast'.

"After I got bigger, he quit taking me out of the cage at all. He kept me chained, a manacle around my ankle attached to a ring at one end of the cage. It had got to where I could smell the sleeping powder in my food, and I'd just throw it back at him. After that, he never let me out, just used a hose to clean up the cage every day, threw some food in afterwards.

"Every night, he'd open the big gate at the end of the cage, far enough away that I couldn't reach him, chained up like that. He'd whip me so, just before a show, all he had to do was show me the whip and I'd get good and mad. He liked it when people would back away, scared of me. He would laugh and say they'd come back and bring their friends to see his 'fierce beast'.

"That's how it happened. One night he opened that gate and started in on me with the whip. He laughed while he did it, taunting me for a stupid animal and cutting me across the back and shoulders until I bled through my fur. I always figured he'd make a mistake and kill me one time, or maybe it wouldn't be a mistake. He kept at it until I could hardly think for the pain, and when the chain broke, I didn't know at first that I was free.

"I was cowering back in the corner, and then I made a run at him, like I always did, but this time the chain didn't jerk me back. There was only a little tug on my ankle and then nothing. The chain was iron, and I guess it rusted out from all the water over the years." He stretched out one leg, and I saw the old and corroded iron bracelet around one ankle, still holding a single link of chain. "Anyway, he stepped back when I got close, then brought the loaded whip handle down on my head, trying at the same time to close the gate. But I was there by then, and all I could think of was I'd stop him from hurting me or anyone else ever again."

I put out a hand, but this time he flinched away. "He was an evil man, Tommy, cruel, and he liked causing pain. But I killed him. I'm a murderer."

"It was self-defense!" I cried.

He stared at me, golden eyes empty. "Do you think that the law is going to look at me the way I am and give me a fair trial? They'll just shoot me, like any vicious animal."

I just sat there a moment, the piece of rabbit forgotten in my hand. Then I looked up at him. "There must be more. Tell me exactly what happened," I said, and after a few blinks, Richard began at the beginning.

"At first, when I was still small, he kept me in the same cage with the leopards. I think he wanted us to fight, but we all just cowered away from him and that whip. When he left us alone, the leopards would curl up together in a corner, and after a while they let me curl up with them. They licked each other for comfort, and I'd purr too when one of them washed my face, as though I were a cub. When he was gone, I'd talk to them, and they'd go still and stare at me, almost as if they understood. They were my friends, the only friends I had, and I hated it when I got bigger and he put me in a separate cage.

"I remember when Maisie, the oldest female, had kittens. I don't think she would have had them, knowing the life they'd lead with him, but it was instinct and she couldn't help it. The kittens were so cute and fuzzy. If our cages were close enough, I'd reach out and pet them, and they'd chew on my fingers. When they grew up, it was almost like we were siblings. I'd got to where I understood a lot of their growls and movements, and we took care of each other, as much as we could, sharing food and making warning sounds when we heard him approaching."

Richard stopped and looked around the dark landscape, almost like he was looking for his friends. In my explorations of the swamp, I'd smelled some kind of small cat but hadn't given it much thought. Every place had wild cats.

He shook his head, reaching out to break off another piece of rabbit. "I miss them, Tommy." He sighed.

"That last night, I kind of fell out of the cage after he hit me and right on top of Ivanov. He yelled out, and all of a sudden he went quiet. I guess maybe he hit his head. The first thing I did was grab the whip out of his hand and throw it as far as I could. It seemed important to rid him of the weapon that he'd tortured me with for so long.

"I was feeling kind of dazed, and I thought about just running away into the night, but I heard the leopards screaming, and I couldn't just leave them there. There was a padlock on their cage, and I made soothing sounds as I went over to them. Ivanov must have had keys for it somewhere, but I just picked up a big rock and started hammering at the lock, and it broke open quickly. Only three of my leopard 'brothers' were left. The others had died over the years, from poor treatment and despair. When the cage door swung open, they leaped out and started stropping against my legs, purring and making little cries. I crouched down and put my arms around them, so glad I could touch my friends again. Then one of them growled, and I felt something hit me across the back of the neck. My vision started to go red, but I turned, growling too, just in time to see Ivanov with a heavy piece of wood in his hands. I extended my claws and reached for him, and then all I saw was blackness.

"I must have passed out, and when I woke up Ivanov was dead, all bloody and claw-marked. Max, the biggest leopard, was licking my face, and I realized that I had smears of blood all over me. Max gave a little trill when I sat up, and he nudged me with his shoulder, then walked to the opening in the tent wall where his brothers were waiting. I could see the rest of the camp, all dark now, and no sign of dawn yet in the sky.

"Later on, I wondered why no one had come when the animals were making so much noise, but no one with the show liked Ivanov much, and he always camped away from the other animal acts. I guess everyone was used to the sounds we always made when he used the whip."

Richard looked a little dazed when he finished, staring down at the piece of rabbit in his hand like he'd never seen it before.

"So," I said, "what makes you think you killed him?"

He twitched and turned wide eyes to me. "What do you mean? I was right there, practically on top of him. I didn't look at the body too closely, I just wanted to get away, but I knew he was dead. He smelled dead."

Richard's eyes took on a faraway look. "We ran, the leopards and I. There were plenty of woods nearby, and we ran together until dawn. I could hardly keep up, my head hurt so, but they stayed with me. When it got light, we climbed into trees and slept there until it was dark again. That night, we took turns licking dried blood off each other. I remember it made me painfully thirsty, and I began to search for water. We found a stream, and the leopards crouched down to drink, but I was dizzy and feverish and I must have fallen in. When I woke up, it was getting light, and I had washed up on the rocks downstream. The leopards were gone."

He rubbed his eyes with one hand. This time when I reached out to pat him, he didn't pull away. I didn't want to tell him that the telegram had said the sheriff and his men had killed some leopards. He'd learn that soon enough.

I could hear waves. From the sound, I figured the beach wasn't far. Wiping rabbit grease on my pants, I stood up. "Come on, Richard. I want to see the water."

He tilted his head to one side, like I'd said something he couldn't understand. Then I held out one hand, and he took it.

We lay together on the little beach as the almost-full moon slipped down the sky to vanish below the waves. Or maybe it was us who slid away from the moon. I knew he was asleep in my arms, the blanket from my pack snug around us against the chill. I stroked my fingers across the soft fur of his back and shoulders. Underneath, I could feel the uneven ridges of scars, and I was glad Ivanov was dead, whoever had killed him.

I held Richard tight, my arms a band of protection, keeping him safe from bad dreams and boogie men. I knew I'd protect him from real things too, the law and anything else, if the time came.

Was the law really searching for him, like he feared?

If they wanted him, they'd have to go through me.

I meant to stay awake all night, but I must have fallen asleep, because I woke up in the first light of dawn. Richard was still asleep, but hot breath blew in my ear and something wet swiped across my cheek, and when I opened my eyes I was face to face with a pair of yellow ones set in a furry, spotted face. The leopard and I regarded each other for a bit, and then I nudged Richard.

"What?" he said, snuggling further under the blanket.

I poked him and motioned toward the big cat, who was now making sort of a bass purring noise. "Friend of yours?" I asked.

Richard's eyes opened wide. He cried, "Max!" and all of a sudden the leopard pounced on him, which meant he pounced on me too, and we all rolled around on the sand for a while until I managed to extricate myself from the furry, growling ball. Neither of them were wearing clothes, but Pa and Papa get upset if I tear mine too often.

It was a struggle, getting Richard to go back to camp with me. Still, I had an answer for every one of his objections, the main one being that he knew I could track and catch him again if he ran away.

"What about this chain on my ankle?" he asked as we walked along, him clanking a bit with each step.

"Pa has tools that will make short work of that," I told him.

I had time to note that Richard was slightly taller than me, but only slightly, though he was a year older. My guess was that he hadn't been eating as well as I had for the past years.

Max loped happily along beside us, making the occasional trip into the bushes but always returning to Richard's side. I wondered what Pa and Papa would think of a leopard prowling around our carnival. Somehow, I didn't think Richard would want to see Max in a cage again.

"Where do you suppose he's been all this time?" Richard asked, watching the big leopard leap into the air after a butterfly. "And where are the others?"

I knew Richard didn't really expect me to answer, and I was glad. I thought I knew what had happened to Max's brothers. "I guess he's just been following you," I said.

"Yeah," Richard said thoughtfully.

We created quite a stir when we got back to camp. I took Richard right to Mr. and Mrs. Lacey's wagon, and they were both there. You never saw so many hugs and kisses, but Richard just seemed to soak up every one. He'd been a long time without human companionship and love.

Mr. Lacey himself sawed the iron bracelet off Richard's leg, cussing all the while under his breath. Richard seemed to stand a little taller when it was gone.

His folks even welcomed the leopard. Max showed no interest at all in the horses, and after a few days and some outraged snorts, they took little notice of him. Of the other carnival animals, the lions and tigers were the most upset, but I figured that was because they wanted to be out of their cages too. When the marks come to see the show, Papa walks Max around on a leash with a jeweled collar. The marks love it, even if Papa never allows any of them to pet him.

It took Richard a while to figure out how he felt after hearing what the sheriff had written to his mama. His folks told him they were sure that the leopards had killed Ivanov and that he'd deserved it for what he'd done to Richard. But I'd catch him with a far-away look in his eyes sometimes, and I figured I knew what he was thinking about. Then I'd just sit with him, and Max would come and curl up too, and after a few days I think Richard started to believe the story. He seemed to feel a lot better about things.

Me, I didn't care one way or the other. I would have killed Ivanov myself, back in that tent, if I could have.

After his mama and papa got used to Richard being back and would let him out of their sight, he and I would go off together. I showed him all of my favorite places, and it was great having someone who not only liked the same things I liked but could hunt and keep up with me when I ran.

Richard's mama never stopped talking about how skinny he was, and she fixed all his favorite dishes from back when he was a little boy. The other women in the carnival seemed to agree with Mrs. Lacey, and they slipped him biscuits and cookies and candy whenever he passed by their wagons. Papa even went out of his way to offer Richard extra food, and I never saw him turn anything down. I had to stifle a giggle when his mama had to let out the pants she made him wear.

Things settled down to a routine, and it was getting on to spring and time for the show to get back on the road. I got up every morning with a smile on my face and went to bed tired and happy from working and playing with Richard all day. As far as I was concerned, life was just about perfect. I should have known it couldn't last.

One nice warm day, Richard showed up with a picnic basket his mama had packed. I could smell that it was full of fried chicken and potato salad and fresh bread, along with at least one berry pie. By now, I was pretty fond of Mrs. Lacey's cooking too, or Cousin Sasha's, as she liked me to call her. Richard and I headed down to a little stream that fed into the waters of the bay. We'd eaten most of the food and had one piece of pie each before Richard told me, which was a good thing, because I probably would have lost my appetite.

"Mama and Papa are going on tour to Europe," he said out of the blue. "Some earl or duke or something wants them to perform for him. They've gotten offers before, but they said they always refused them." He smiled a little. "Because they were still looking for me."

I jumped in. "You can stay with us! Pa and Papa won't mind, and there's lots you can do for the carnival. I bet you could help with the big cats, and…"

Richard held up a hand. "I want to go with them, Tommy. Mama says things are different there. She thinks maybe people will accept me for who I am, not call me a freak. Maybe I can even go to school, a real school. Tommy, I barely know how to read."

"I can teach you how. And the Professor and Hattie…"

"I know they're good teachers, but I want to learn more, Tommy. Maybe go to a university and become… something… a doctor, maybe, or a lawyer."

Richard's eyes were shining, and he wasn't looking at me anymore. I could tell he was already seeing far-away places and beautiful dreams. I studied the ground at my feet. Hattie and the Professor were the only teachers I'd ever had or ever thought I'd need. I sighed. But with the life he'd lived, I guessed I couldn't blame Richard for wanting something else, something more than a carnival.

He put a hand on my arm. "There's another reason too. Even though no one seems to be looking for Ivanov's killer, Papa thinks it would be good if I were out of the country for a while."

I shrugged. "Sure," I said, "that makes sense."

He grabbed my shoulder and shook me a little. "Maybe you can come visit me."

I glanced up, then back down. "Maybe." I wasn't sure how that would work. Europe was a long way away.

Richard put his hand on my cheek and turned my face toward his. "Tommy," he said, "you're my brother. I never said I was staying away forever. I'll be back." And then he hugged me.

Max, the leopard, did not go to Europe, but he is always interested in every letter Richard sends me. He sniffs them and purrs, and he even seemed to enjoy the photograph I got in the mail last week, though I think it was more the smell than the picture. I found a thumbtack and stuck it on the wall above my bed, and Max and I look at it every night. I almost can't believe my eyes, because Richard is wearing a suit. It seems to fit him well, though he says it's murder keeping his tail down one of the pant legs all the time. He's wearing a hat too, and his hair is still long and flows down over his shoulders, which he says is very avant-garde, whatever that means.

He tells me he isn't afraid to walk alone in the streets of Paris, where they are now, and that the teachers at his private school find him a "fascinating curiosity," which sounds a lot better than "freak."

Sometimes, when I read one of Richard's letters, I wish I was in Europe, though I'd never tell Pa and Papa. Anyway, I know I'd miss all my friends if I left the carnival.

I know Richard is learning a lot, and I look forward to hearing all about it one day.

Richard has made a promise to come back… and Max and I are going to hold him to it.